11. Short, Happy Wife. Eleanor de Vailles-Villages

Five long and convoluted plots make up the majority of this restoration comedy. The major thread running throughout turns the usual rakishness on it’s head and postulates a Female Falstaff, a direct descendant of his who has been given the rather unimaginatively named Duchy of Notwit (a corruption of “not wet” typical of the most ostentatious restoration sexual jokes).

She sets out to outdo her famous relatives apparent seduction score of seven. She manages three during the action of the play, but the epilogue suggests there were originally several more plays within the cycle that either have been suppressed or were lost with the changing of theatre-going appetites. Two of the three main men seduced by the Duchess of Notwit are involved in an ongoing feud over a woman who is one of the Duchess’ intended targets.

The Duchess of Notwit, in one rather pleasing “banquet scene”, offers a defense of epicurean delight, suggesting to one of her lover’s that they might be delighted in perpetual edibility. This scene informed Salvador Dali’s development of Les Diners de Gala.

Everyone seems to have a romantic dalliance with everyone due in part to some plot they have explained in detail to their servants, who all operate as the Plautine style clever slave, which means the plans they make keep tripping over each other.

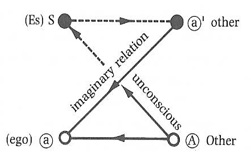

Jaques Lacan’s original notes towards his Seminar on “The Purloined Letter” indicate that he meant to use the signifiers present within this play, but his diagrams in the manuscript ballooned further and further outwards into a ball of arrows all connecting back and forth with each other. He attempting several times to piece out the plot of this play, only to give up each time: the essence of the signifier escaped him, always seeming to be some other.

Most of the other plots likewise involved the sexual politics of the day, and are less well regarded, with the exception of the woman who dresses in male breeches who is revealed to have been a male actor all along to find that the person she settles for (instead of her intended amour, who chases Notwit) was

“born between the sexes, preferring both, taking on either when needed, but appealing to and aspiring to a difference of none.”

This pun is further taken into lasciviousness by the immediate retreat of the two lovers to a far off convent– an idea picked up later by The Marquis de Sade.

As for the authorship of this play, it is suspected that de Vailles-Villages is a cipher for some peer of the realm, a regular at court, who is writing en femme (which, rather jou·is·sance-lly ) may indeed have been the writer’s position at court, the King’s official girl.

10. Against the Gardens.Henry Callhoon (or Cwalhoom)

The attribution and scholarship of this is in some doubt, but best guess suggests that Henry Callhoon, a soldier in the New Model Army penned these lines.

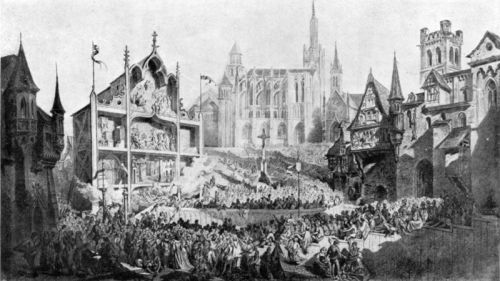

A piece of pro-protectorate propaganda, exalting Oliver Cromwell and his political order. Specifically, the target here is excess on the part of royalty (whether imagined or not), precisely for taking up and using space that Callhoon feels would better serve the nation as farm, vegetal, and working gardens to aid the country.

The gardens are described with some grace, and a hint of jealousy– readers often comment on the specific ire target towards certain statues whose presentations take up long, assiduous asides. Callhoon cannot prevent the reader from feeling the beauty of the statues that he celebrates being knocked down: though there is a beauty too in the destruction of beauty, which he captures in a final canto, the argument of which reads

“Though there be things of beauty in this world; if they are made in service of evil; the more beauty is it that they perish; for those evil things, howsoever beautiful, must be rid from this world; that this world might faschion better beauties.”

Scholars have long debated whether the misuse of the semi-colon even in the arguments to each canto are intentional or a minor fault on the part of the poet: this makes up some seventy percent of the exegetical contentions on the poem. That scholarship is too obscurantist and too deeply technical to go into here.

Finally, it is important to note that none other than Andrew Marvell at first wholeheartedly agreed with this poem, but turned against it when politically opportune during the restoration.

“Taken with the republicanism of my youth,” he wrote, “I believed that such destruction might make a better freedom in this world. Now, penitent and in the service of the rightly restored monarchs, I do not know how to respond to such destruction.”

Evidently, this problem continued to plague his mind until he decided that all gardens were the problem and this did not come from any human fault except the existence of original sin. To be human is to create destructive works, to misused nature. He fully expanded his ideas in the much better noted “The Mower Against the Gardens”. It is to be supposed, however, that the germ of his idea came from Callhoon.

9. A Swiving. John Donne.

A cycle of sonnets written after the death of his daughter, lacing the ever present specter of death (on his mind as well, due to his own health problems) with an urgent call for Englishmen of all types to breed and populate more. Deep in the heart of these poems is the desire to inspire new life in others and achieve some fame and immortality through that inspiration.

There is a deep despair in the works, and this– perhaps combined with the increased eroticization of certain body parts in the text led to the suppression of this incredible sequence. The words are much more akin to that of John Wilmot, more direct in their scandalous nature. There is no doubt that a highly regarded church figure in possession of these poems, much less having written them, would have lost all face and position.

This is why, numerous scholars of note have made clear, the texts were suppressed. Beyond that, much of the work resists binary thinking and deconstructs the ideal of the erotic into a celebration of the baseness of the sexual act. Of note especially is the infamous (and intentionally mis-metered) couplet,

“Let skin touch skin where skin has touched

in breath you draw a God is as much.”

In particular, the “God is” / “Goddess” pun has been noted and deconstructed by many Critical Theorists, but special attention had been paid by Michel Foucault and Annette Kolodny, respectively.

7.The East Americas. Walter Riley.

It is important to begin with a distinction that The East Americas itself refuses to make clear. I quote from the great literary historian, Sir Wailough Ferndale:

“It is unequivocally untrue, on the balance of things, that Walter Riley is merely a cipher for Sir Walter Raleigh. Rather unknown, Mr. Riley’s travelogues only exists as an exercise in imagination, more akin to More’s Utopia than any real travelogue. Riley’s prose style is entirely his own, and bear’s no relation to that rather famous, and real explorer. At best guess, Riley was a barely literate shipping clerk inland whose closest exposure to anything outside of his town came from listening to merchants in the nearby taverns” (History of Walter Riley, Vol. 73).

The East Americas suggests that if Columbus had only sailed the opposite direction, using a specialized boat to sail over the land-mass, a kind of land-ship that Riley spends several chapters describing in great detail, down to a dramatized debate over the best kind of wood to use, he would have discovered, within Upper Mongolia, an America precisely opposite to that described by true adventurers to the newly discovered world.

In the most widely cited chapter, which is very much based on Montaigne’s “On Cannibals” and must later have influenced Swift’s own satire, where he suggests that the people of this Eastern America eat those who are not very ill. They never “touche a jotte of fleshe that rottes,” but instead prefer to keep themselves slightly sick as when a person has not a touch of death about them they are immediately cooked and eaten.

The rest of the book is rather pedestrian, and many of the descriptions are unimaginative re-tellings of Utopia. At the final point, however, Riley’s projected character is loath to leave the East America’s behind. He looks backwards and suggests that there might not be something so different in their strange ways after all:

“we eate of each other ourselves, but have not the honesty to enact it in truth.”

6. Being a True History of the Kings and Queens of England

In reviewing the sources of this period, one name will always stand out: that of William Shakespeare. But this history, which stretches on for several days if performed directly through every act and chapter, is said to have helped inspire the creation of his more popular histories. Sadly, the author remains unknown to time.

While Shakespeare’s histories side with the victors, and are undoubtedly propaganda, this earlier source takes a somewhat opposite thesis to his. Where he demonstrates that the thrust of history can cause anyone to raise to the appropriate level, the True History consistently portrays monarchs as no greater or less inept than any other humans. This, as well as the multi-day running time, led to the suppression of this drama.

Curiously, the Puritans that would so soon ban theatres, mined this dramatic source for every bit of information that might add to their cause. One surviving scrap of a broadside parodying the production of this play claimed

“it is greate in the sweepe of historie only in so much as it is more longwounde than a sermone at some grande churche”.

5. A World Blazon’d. Sir Phillip Sidney.

Pre-figuring his successes with Astrophil and Stella, and before his epoch-making Defense of Poesy, Sidney attempted to take for his subject the whole of the world. Using the Italian form of the sonnet, he sets out not to refigure the sonnet into a deeper, more spiritual level than that of Petrarch, but rather extend the beautiful comparisons outwards to the whole world.

In practice, the eventual Puritan reveals something of his younger, libidinal self, as each extension to the outer world becomes a reversal of the standard poetic shorthand often invoked in sonnet and blazon form. Great mountains with a stream running through them, for example, are compared to a village woman of great endowment. In an epic turn within another poem, as if foreseeing his own death, he does not make the usual comparison of love as dying within the romantic other, but compares loving one another to discovering oneself already dead in some brutal fashion.

Most strange, perhaps, is that clear markings on the manuscript improving the meter and adding racier turns of phrase have been attributed to Sidney’s sister, the Countess of Pembroke.She corrected his metrics and also rewrote several times the death-connection in the aforementioned poem.

4. The Economicks of History. John Milsparre.

A drama in the great Elizabethan tradition, which proposes to take up the study of all of history through a look at a banker named Joham who has discovered a small draft that enables him to stay “unaged endless through and for all un-ending time”.

While navigating a typical romantic plot of bride-switching and love-hate relationships picked up later and improved by William Shakespeare, the main character relates how he has developed into a very wealthy man. The drama ends with a love triangle resolved in a way almost pre-figuring the comedies of Billy Wilder, where having vowed to use up his money to try everything, Joham agrees to marry a cross-dressed younger man (who scholars of the history of costuming say resembles nothing so much as the young Elizabeth). The play ends with the oft quoted lines

“I’ve lived a thousand lives, and loved so many more,

and learned no perfectness in those adored”.

Milsparre was drawn and quartered after the premiere performance, an event possibly attended by both Shakespeare and Marlowe, as it is presumed to have happened near the Mermaid Tavern. One rather brutal critic attributed this killing not to the political and satirical commentary the play raises, but rather to the dreadful misuse of the meter within the text.

3. No One

It is no surprise that this play, which is most likely a translation from a French traduction of Everyman, was quickly and quietly suppressed, The only known copy was found among the belongings left behind by J.K. Huysmans’ lifelong companion, correspondent, and co-oblative of the Abbey of St. Martin of Ligugé, Durtal.

Point by point, No One negatively refutes the main ideas of Everyman, with special animosity towards the idea of confession. The God presented within the play is more akin to the bumbling antics of the ancient greeks that the staid and stoic presentation known to most miracle plays. The major thesis of the work is that Good Deeds are in deed pointless, and as no man may know and understand God while living, it is up to each man to find meaning in his own life.

While not rejecting the idea of divinity completely, No One comes closer to suggesting a demiurgic, evil God. At one point, a sort of proto-Electionist rhetoric comes to the forefront, but takes as the conclusion the unknowable as justification for neither worrying about nor trying to actively please a deity. The drama ends with the figure of God, wounded, flailing about desperately in hopes of some salvation.

1. Céostan

A repressed telling, written certain years after Beowulf, containing the battles of a mainly female warrior clan in direct opposition to the invading Angles, Jutes, and Saxons. Instead of the heroic journey and eventual death due to hubris proposed in the earlier poem, this telling of the classic story of a band against outsiders suggests a quiescence to the eventual fact of loss.

The death count within even the existing fragments is thousands upon thousands before the titular heroine is defeated at last. But she does not remove from life without inflicting a grievous wound on her opponent. She does not gloat, nor does she relish the victory, as it is pyrrhic at best: all her allies are gone and her land is dead.

In a compelling final installment, she rips out the heart of her victim and eats it to absorb his life, memories, and wisdom.

Alternate Non-Canon 1- The Swytche

The Swytche, translated by Cora Chalmers. Began as a simple translation of a side story left usually omitted from The 120 Days of Sodom of a forced relationship, it blossomed into something much longer in the telling. The manuscript was originally only circulated amongst aristocracy, but it’s discovery and publishing under the auspices of Virginia Woolfe thrusted it into a spotlight on the 20s. Amy Lowell and HD praised the book, but Ezra Pound rejected it as further evidence of the “Amygist” betrayal of Imagism. E.E. Cummings copy contains line by line annotations.

The heroine of the novel, which often imitates Radclyffe Hall in the more sentimental scenes, switches back and forth between victimization and victimizing, deriving a great deal of pleasure in these endeavours. However, unlike the later attempts to wedge a new form into the Sadism and Masochism combination, a la Dalinian cledalist philosophy, the heroine really only derives true pleasure from identifying the erotic desires of others, playing along with them, and then switching to whatever the opposite of that desire might entail. This extends far further than de Sade’s contribution, which simply meditates upon a connection between a birch rod and the double-identified users of that rod within sexual gratification.

The heroine, who becomes known as “The Swytche” throughout the story, actually completes the holy triad of BDSM by always being exactly what the other person fears the most– which usually means giving that person exactly what they have asked for.

Slavoj Zizek has used this work as a reference point especially when discussing the big Other.